Introduction

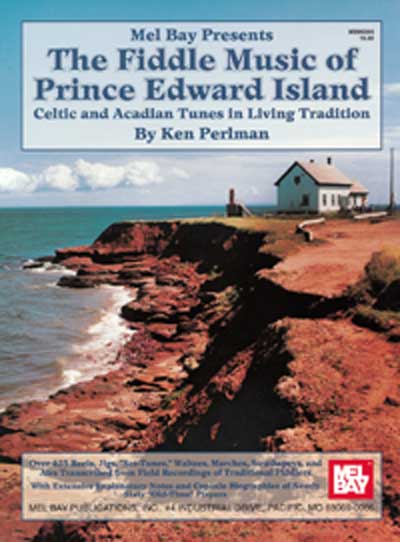

from The Fiddle Music of Prince Edward Island

(Mel

Bay Publications)

by

Ken Perlman

|

. . . from eFolkMusic: " . . an active folklorist, Ken has spent over a decade collecting tunes and oral histories from traditional fiddle players on Prince Edward Island in eastern Canada. In both 1997 and '98, he received awards from the Prince Edward Island Heritage Foundation for helping to "preserve, interpret, and disseminate our province's fiddling heritage." Ken has a web site at www.kenperlman.com/ |

Prince Edward Island is one of

Canada's Maritime Provinces. It lies

in the Gulf of St. Lawrence about 10 miles from the mainland, sheltered within

a "crook" formed by the neighboring provinces of New Brunswick and

Nova Scotia. It is home to about 130,000 people -- almost all of whom are of

Scottish, Irish or Acadian French origin. The Island is divided into three

counties, which are named (going from East to West) Kings, Queens, and Prince. Kings County is most Scottish in terms

of ethnicity and culture, Prince County has most of the Island's

French-speaking Acadian enclaves (such as the Evangeline Coast region), while Queens County has the provincial

capital Charlottetown and much of the tourism.

Prince Edward Island is also home to

one of the oldest, strongest, and most vibrant traditional fiddling cultures in

North America. Despite the fact that the fiddling population has been declining

since 1970, this small Island (it is roughly 150 miles long by 40 miles at its

widest) still hosts at least two to

three hundred fiddle players of a quality sufficient to warrant being

commercially recorded. Moreover, there are easily another two or three thousand

Islanders who can play the instrument

well enough to accompany a dance. This is fully two percent of the population!

Despite this wealth of talent, the fiddling scene on P.E.I. (as locals call it) is virtually unknown to outsiders. In

fact the Island is far better known

for its beaches and its connection to Lucy Maud Montgomery's famous novel Anne of Green Gables than it is for its

fiddling.

Little did I know when I first set

foot on Prince Edward Island in the summer of 1989 that I would spend the next

several years deeply immersed in its music. All that immediately struck me

about P.E.I. was that it was very beautiful. Everywhere I looked were fields of

flowers. Intensely green foliage contrasted favorably with a deep rust-colored

soil. Even more striking were the brilliant red bluffs that lined the shore

along the Gulf of St. Lawrence, not two hundred yards from my host Dan Gillis'

front door. And although my host had led me to believe that I might meet a few

fiddlers during my stay, it didn't seem that this corner of the Island --

Northeastern Kings Co. near the town of Souris (pronounced SOO-ree) -- had a

lot going on. There were just a few houses clustered together every so often

along the road, a few farms, a couple of fishing villages, and lots of

new-growth spruce.

A

series of events over the next several days quickly altered this last

assessment. A visit to a local town-day called the "Monticello Tea

Party," produced a meeting with several fiddlers, one of whom -- George

MacPhee -- was to provide me an introduction to the fiddling scene along the

"North Side" of Kings Co. A chance inquiry at a Souris gas station

produced my first contact with the Chaisson brothers -- Kenny, Peter and Kevin

-- who turned out to be the best known proponents of traditional fiddle music

on P.E.I. Then things began to really move fast. A musical evening organized by

my host was attended by Mr. MacPhee and several local fiddlers. A day-long

movable jam session with Mr. MacPhee enabled me to meet several of his fiddle

playing sisters. A weekly meeting of the Northeast Kings Co. branch of the

P.E.I. Fiddlers' Association brought me into contact with still more

top-quality players.

I had just met more expert fiddlers in the last five days, than I

had encountered on my travels in the States in the last five years!

"Why" I kept asking myself on my way back to Boston, "have these

people never been recorded?" I vowed to do everything in my power to

rectify this situation.

In

the summers of 1991-2 -- with much assistance in terms of funding and volunteer

labor from the Earthwatch Organization of Watertown, Mass. -- I was able to

record on both audio and video tape close to one hundred high quality fiddlers

from dozens of Island communities. Most of these musicians were taped in their

own kitchens with their families and favorite accompanists in attendance. I

came away from this experience with the feeling that these artists were every

bit as unique and musically intriguing as any folk-instrumentalist I had ever heard

on an old 78.

About This Book

Once I had the recordings in hand I

set to work with my trusty Marantz tape recorder and its helpful half-speed

feature. Tunes from about sixty fiddlers -- ranging in age from 13 to nearly

ninety -- were selected to be transcribed

(written down). Each selection was transcribed from tape as that fiddler played it, with as much precision as I could

muster. When the transcriptions were completed, I transferred them to computer

via a program called Finale.

The 427 tunes included in this

collection represent a large proportion of the current Island repertoire. Well

over one hundred of these tunes have to the best of my knowledge never seen

print before, and perhaps a like number have appeared only in privately printed

books of relatively limited circulation. Even those tunes that have appeared in

many previous collections often feature new and intriguing details.

Because each tune is a transcription of a specific performance

by an individual player, many subtleties of style -- such as ornamentation,

double stops, and slurs -- are included (see "The Prince Edward Island

Playing Style"). Also included are each player's melodic idiosyncrasies --

called twists in local parlance (see

"Regional and Individual Styles"). You won't find, therefore,

"definitive" versions of fiddle tunes in this book. You will find

living, breathing versions of tunes filled with the vitality of a people whose

great love for their music is expressed in every bow-stroke.

In essence then, The Fiddle Music of Prince Edward Island

is a collection of about 425 fiddle arrangements or settings. Each setting is a record of the musical techniques and

nuances put into play by an individual fiddler on a given day. Because these

techniques and nuances are derived from a common pool of experience, these

settings taken together give a fairly clear picture of traditional fiddling on

P.E.I. as it exists today.

I am well aware that most tune books

offer merely a basic version of a tune

-- what might be called a tune skeleton.

In other words they offer a melody line with little in the way of musical

nuance. The advantage of this skeletal

approach is clarity -- the tune is right there in front of the player

without any distraction or encumbrance. This is only an advantage, however, provided that he or she knows the tradition

well enough to put in the kind of subtleties and elaborations that make the

tune come alive.

In fact, to a bred-to-the-tradition

musician, a "tune-skeleton" is more than sufficient. They don't need

the subtleties put in, since they already have their instincts to guide them.

In fact, they would rather avoid the distraction of someone else's subtleties

in order to fully concentrate on putting in their own. Those not bred to (or

not conversant with) such a tradition, however, sometimes have a tendency to

treat a tune-skeleton as if it were the whole story. This can result in a

rendition that lacks vitality.

This book serves a number of

functions. First, as stated above, it aspires to create a relatively complete

picture of the contemporary P.E.I. playing style. Second, it serves as a guide

to those who wish to emulate that style. Third it can easily be adapted to

serve as a conventional tunebook -- both for those musicians who are already

conversant with the style, and for those who are merely interested in the

Island's melodies for their own sake.

Because "clarity" is such

an important issue in a tune book, every effort was made when setting these

tunes on computer to come up with a format which allowed for a clearly visible

melody line. To this end, all melody notes are left full-sized, while notes that form the non-melody part of a

"double stop" are presented in substantially reduced size (see

"Special Symbols"). The eye can easily scan any transcription and

come up with its tune-skeleton. Moreover, those merely interested in a

"skeletal" melody line can also without difficulty ignore

ornamentation, slurs, and other playing directions.

Six of the tunes transcribed here

were not recorded during the 1991-2 taping program. First, the tunes played by

Lem Jay -- "Lem Jay's Fancy*," and "Kitty at the Well" --

came from privately made 78-RPM recordings in the possession of his son Roland

Jay. The tunes composed by Kevin Chaisson -- "Karen Chaisson's Reel,"

and "Bear River Jig" were recorded on piano in August 1993. Finally,

the strathspey "King George IV," and the reel "The

Honeymoon" were recorded respectively by Peter Chaisson, Jr. and Archie

Stewart in August 1994.

Fiddling on Prince Edward Island

Once you learn where to look for it,

"old-time fiddling" (as the

locals call it) is nowadays very much in evidence on P.E.I., especially during

the summer. The Rollo Bay Scottish Fiddle Festival, held the third weekend in

July in Northeast Kings County draws crowds of over 5,000. The Atlantic

Jamboree and the Acadian Exposition (held in Abram-Village, Prince County the

first weekends of August and September respectively), draw several thousand

people each to the fiddle concert portion of their programs. The Queens County

and Prince County Branches of the Prince Edward Island Fiddlers' Association --

whose performances feature ensemble playing of fiddle music -- are in constant

demand. Town days, benefit concerts, ceilidhs,

(pronounced KAY-lies: Gaelic for "musical evenings") and smaller

festivals dot the Island. In addition, there are a number of venues where

old-time square dancing takes place on a regular basis.

Island fiddling is a lively blend of Scottish, Irish and

Acadian-French elements. Local tradition has it that the first boat-loads of

Scottish immigrants landing at Tracadie Bay on the northeast shore of Queens Co. in the late eighteenth

century had fiddlers among them, and some families can trace their musical

pedigrees back to that time. The Irish appeared in substantial numbers perhaps

a generation later, and added their tunes and playing style to the mix. The

Acadians are almost all descended from the thirty-odd families allowed to

remain on the Island when most of their countrymen were expelled by the British

following the Seven-Years War (1756-63). They have adopted the tunes and

overall approach to fiddling of their Celtic neighbors, but many --

particularly those who grew up in western P.E.I. -- have their own notion of

style and sense of rhythmic nuance.

The Island fiddle repertoire these

days is a hodge-podge of tunes from a variety of national and regional

traditions. Its core is Scottish and -- to a lesser extent -- Irish, but it

also includes tunes from Cape Breton, mainland Nova Scotia, New Brunswick,

Quebec, Ontario, New England and the Southern United States. In addition, there

are many tunes composed on the Island, and versions or variants of tunes "from away" that have evolved among

Island fiddlers over the generations. (see "The Island Repertoire").

What is unique about old time

fiddling on P.E.I. is not so much the repertoire -- much of it as we have seen

is shared with other fiddling traditions -- but rather the manner in which that

repertoire is played. And, although there are several distinct regional playing

styles on the Island -- and the argument has often been locally made that each

Island fiddler is a style unto himself -- there is nevertheless a distinctive

"sound" that is characteristic of nearly all Island players. There

are also a number of playing devices and techniques that are virtually

universal.

The Island fiddle sound reflects

directly the subtle rhythmic nuances of square and step dancing (see

"Dancing to the Old-Time Fiddle"). In fact, the playing of a "good

fiddler" is said to convey a rhythm so infectious that anyone within

listening range will want to get up and dance. Island fiddlers tend to have a

full, strong yet sweet tone. To this writer, listening to the rolling sound of

an Island fiddle is like watching the clouds go by on a summer's day -- the

music rises above the cares of everyday life and offers a sense of freedom. For

more on these subjects, see "Regional and Individual Styles," and

"The Prince Edward Island Playing Style."

Fiddling in the Old Days

It is no accident that there are

hundreds of top-quality fiddlers on P.E.I. Because of a variety of historical

factors -- not the least of which was a

long term policy by the Canadian Federal Government that promoted growth in the

center and west of the country while ignoring the east -- P.E.I. was long an

economic and cultural backwater. In fact, many technological advances that

urban North Americans take for granted -- such as electricity, paved roads, and

automobile travel -- were not a part of rural Island life until the 1950s.

Prior to this time, people rarely travelled more than a few miles (a

comfortable wagon or sleigh ride), and communities were responsible -- not only

for maintaining their own livelihood, but for organizing and conducting their

own entertainment.

In them days virtually every community had its own stock of fiddlers,

who supplied the music for the dances that served as the primary form of

recreation. The most common venue for these dances was the informal house party. Word would go out that the

event was in the offing, a kitchen would be cleared, the fiddler would set

himself up in the corner, and the neighbors would gather together for an

evening of square sets (as the local

variant of square dancing was called) interspersed with episodes of a solo

dance form known as step-dancing (similar to Southern

clogging and Irish stepdancing, but closer to the floor than the latter and

with less upper body movement than the former). As Archie Stewart of Milltown

Cross, Kings Co. recalls:

"Back

then...there was no radios, there was no television, and that was the only

entertainment we had -- in the wintertime probably once a week somebody'd have

a house party. And ... everbody'd bring a pound of sugar and they'd make fudge

and we'd have fudge and then they'd clear all the stuff out of the kitchen and

I'd get the fiddle out and away they'd go and they'd dance 'till 12 or 1 o'clock and that was an evening's

entertainment. There was nothing else! And it was good pastime."

Not only did fiddling and dance

provide "entertainment," but they also served other important

functions within the community. When money had to be raised for the up-keep of

the local school house, the community held a fiddle-dance. When the local

church needed support, it scheduled dances as part of a tea party or parish picnic.

When a wedding was decided upon, virtually the first act of the families

involved was to line up the fiddler.

"Jigging" the Tunes

Making music in old Island districts (communities) was not just the

province of the fiddler. Most residents knew at least the more common tunes by

heart, and a fair percentage excelled at an activity known as tuning or jigging -- singing dance tunes with full rhythmic nuance using

abstract vocables or nonsense lyrics. In fact, many Islanders jigged in full

voice as they went about their daily chores. School children in many

communities would spend their lunch recess jigging tunes and step-dancing to

jigged accompaniment; they would also make a game out of imitating the jigging

styles of community adults. What's more, when no fiddlers were available, tuners were sometimes called upon to

provide music for square dancing.

Learning Tunes

Tunes were passed down between the

generations for the most part by ear within the family and community. Many

fiddlers report that they learned their first tunes by listening to the jigging

of family members. Other opportunities to hear tunes included older relatives

who played fiddle, community dances, and -- by the 1930s -- radio (powered in

the days before electrification by storage batteries akin to those found today

in automobiles). By the time most youngsters were old enough to manipulate a

fiddle, they had already committed to memory a large portion of the local

repertoire.

Learning

new tunes often had to be done on the fly. A couple of hearings at a dance or

on the radio might be all the exposure to a particular tune you might ever get.

Fiddlers developed the ability to absorb the essence of a tune in a couple of

hearings. According to most accounts, retrieving a new tune from memory was

often an unconscious process. A fiddler would awaken in the middle of the

night, be lying abed in the morning, be at work in the fields or on a fishing

boat and a recently heard tune would

appear to him in its entirety. If a fiddle could then be immediately got

hold of, the tune could be picked out and retained in memory. Otherwise it was

lost.

Passing

On the Art

There was no formal instruction in

fiddle technique. What little instruction occurred was devoted to teaching the

notes of particular tunes. Most established fiddlers felt that since they

couldn't read music, they had no guidance to offer a novice. For the most part,

fiddlers learned their playing techniques through imitation of other players in

the family and community.

Perhaps the best place to learn the

fiddlers' art in those days was from the heart of one of the numerous fiddling

families that dotted the Island. In such families, at least one parent and a

large percentage of the numerous children in residence played fiddle,

accompaniment instruments, or step-danced. Not only was music making and dance

continual on evenings and Sundays in these households, but community members

could precipitate a house party merely by dropping in.

Women and Fiddling

In the old days, most of the

Island's few active female fiddlers came from these large fiddling families.

Fiddling was considered by and large to be a man's calling, and those women who

were musically inclined were encouraged to take up the pump organ or piano.

Part of this was simply an extension of other "division of labor"

attitudes that had men running the plows, mowers, and binders, and women

learning to spin, weave and cook. But there was also a general feeling that fiddling

at dance events was no "proper" activity for a woman. As a result,

most Island women who fiddled plied their art primarily in the privacy of their

homes. There was one notable exception to this state of affairs. Since the

1930s, when Zélie-Anne Poirier and her sisters established themselves as lively

dance fiddlers against initial community opposition, women have played

regularly for dances in the Evangeline Coast region of Prince Co.

The Dark Side of Fiddling

Having the gift of fiddling was sometimes

a mixed blessing. Along with the joy of playing came the strongly felt

obligation to share your gift with the community, regardless of how you felt

about it at the time. In fact, fiddlers were expected to offer their services

gratis at house parties, community fund raisers, and (for the most part)

weddings. Some community fiddlers were called upon to play several nights a

week, despite the fact that they were also working from dawn to dusk at farming

or fishing. After many years of this routine, it's perhaps noteworthy that only

a relatively few broke under the strain.

Fiddlers did have the reputation in

some communities, however, of spending too much of their time fiddling and not

enough of it working. Stories abound to this effect. There is, for example a

former settlement in Kings County that is said to now be abandoned because it

once sported so many good fiddlers that no one did any work. And then there's the story they tell about a

well-known Prince Co. fiddler whose long-suffering wife was dismayed one day to

see him head off with his instrument to a house party while several weeks'

backlog of chores were piling up. "How can you leave when there's not a

stick of wood about the place," said she. "Woman, I'm taking the

fiddle, not the axe," said he.

Fiddle Contests

Fiddle contests were once held all

over the Island in the warm months. While people still talk about the Great

Fiddle Contest of 1926 -- when P.E.I. champion Neil Cheverie of Elmira (Kings

Co.) was sent to compete against North America's finest at a competition in

Boston -- most fiddle contests on the Island were modest affairs. Prizes

generally were small, but the prestige of winning was so great that hard

feelings often arose among fiddlers and even among the families of fiddlers.

What's more, these feelings of hostility sometimes persisted for decades. As a

result, the 1970s saw a general movement-- spearheaded by the Prince Edward

Island Fiddlers' Association -- to ban fiddle contests on the Island.

Decline and Resurgence

The mid-1950s through the early

1970s saw great changes come to the Island -- rural electrification, mass

communications, improved roads, widespread automobile usage, mechanized

agriculture, and school consolidation. It was now possible to seek work and entertainment

outside the community in which you lived. For the first time, the focus moved

away from community music and dance to entertainment provided by mass

communications. Hundreds of community fiddlers -- products of a tradition that

had provided dance accompaniment for generations -- were still in place, but

their talents were no longer in constant demand. As the importance and

visibility of fiddling declined, the art no longer drew youngsters to its fold.

By the mid-1970s Island fiddlers were an aging population with few members even

as young as 30.

By the late 1970s some fiddlers on

the Island became sufficiently alarmed by this state of affairs to do something

about it. Under the leadership of a priest from Little Pond named Faber

MacDonald (then posted in the Charlottetown area and now a Bishop in

Newfoundland), Joe Pete Chaisson of Bear River, and several others, the Prince

Edward Island Fiddlers' Association was formed -- in part to address the issue

of passing the art on to the young. Eventually, branches were organized for

each county. The Prince Co. branch -- run for most of its existence by John

Gauthier -- was based in Summerside, the Queens Co. branch -- currently under

the direction of Fr. Charles Cheverie was based in Charlottetown, and the

Northeast Kings Co. branch -- under the direction first of Joe Pete Chaisson,

and later under that of his sons Peter, Kenny, and Kevin -- was based in

Souris.

Perhaps the most important activity

of the Fiddlers' Association has been its support for group fiddle lessons

aimed primarily at youngsters. Using proceeds from the Rollo Bay Fiddle

Festival, for example, the Kings Co. branch has sponsored free fiddle classes

every Monday night for the last fifteen years at the Rollo Bay Consolidated

School. These efforts have just begun to bear fruit and a new generation of

players trained at Rollo Bay is just now coming into its own.

Interestingly,

neither the Fiddlers' Association nor the Rollo Bay teaching program has

maintained the old Island prejudice against females playing fiddle. Both Queens

County and Prince county branches have substantial numbers of women playing the

instrument in their performing ensembles. Similarly, females of all ages have

been welcome at the Rollo Bay program since its inception. As a result, there

are fine young woman fiddlers cropping up not only in Kings County, but in

other areas of the Island as well.

Since the early days of its

operation, the work of the P.E.I. Fiddlers' Association has been helped along

considerably by a wave of nostalgia for a rapidly receding past. In many Island

communities, this has led to a revival of such fiddle-oriented community events

as tea parties, ceilidhs, and old-time dances. Another aspect of this phenomenon

was a widespread demand for formal step-dance instruction, as parents around

the Island suddenly felt the need to have their young girls learn the art (see

"Dancing to the Old-Time Fiddle.")

The Future

Although there is reason for

optimism, the survival of old-time fiddling on P.E.I. is far from assured. Most

active fiddlers on the Island are past sixty, and most of them grew up in

traditional settings where formal music teaching was not a part of life. They

are not well equipped to instruct the generation "coming up," even

when there are members of that generation who are eager to learn. And, despite

the great success of the Rollo Bay teaching program, there is still not enough

fiddle instruction available elsewhere on the Island. The great diversity of

the styles and tune versions that form Island fiddling today may yet become a

thing of the past.

Dancing to the Old-Time Fiddle

Fiddling on the Island has always

been associated with social dancing. For most of the Island's history, these

dances were done in what might be termed standard square-dance or square-set formation, with four couples

lined up at right angles. The oldest fiddlers remember dances called breakdowns -- the Scotch reel, the

four-hand reel, and the 8-hand reel --

in which participants actually step-danced through most maneuvers. In

the 1920s or so these dances apparently gave way to others -- like the lancers,

the quadrille, and local variants of the above like the "Souris set"

-- where most maneuvers could be walked through. Thereafter, step-dancing took

the form of spontaneous "exhibitions" by solo dancers between square

dances at house parties and other local dance events.

All these square dances were divided

into distinct segments called "figures." Each figure had different

steps, each was accompanied by a different kind of tune, and each was followed

by a distinct pause that offered everyone a chance to take a breather. Most

fiddlers I spoke to remember that the square dances in their respective

communities had four figures. As time went on, each community evolved its own

version of square dancing which varied from that of its neighbors in terms of

the number of figures, the order of figures, the actual steps done, and the

kinds of tunes played for them.

With the coming of the

"modern" era, the nature of the set-dances changed. Islanders could

now travel greater distances, which allowed dancers from several communities to

gather at a single centralized hall. Since Islanders refused to resort to the

expedient of using a caller (that institution had for the most part been

abandoned by the 1920s), there was no trend toward standardization of figure

order and step-sequence. As a result, hall dances to this day require

negotiation on these matters, and the overall trend has been toward both a

simplification of dance steps and a decrease in their number. In addition, the

pressures of dealing with large numbers of dancers in relatively small spaces

led to the development of what might be termed a circle-formation set dance.

In the circle formation dance --

which is more or less all you see in the current era -- each couple around the

circle forms what amounts to a small square with the neighboring couple. Each

"square" of two couples then goes through the steps of a given

figure. Then the couple on the right passes clockwise through its original

neighbors and forms a square with the next neighboring couple on the circle.

The couple on the left passes counterclockwise and forms a new square with its

new neighbors. Then both new squares go through the steps of the figure.

Although waltzes have been part of

the Celtic fiddle repertoire since the 1800s, there apparently wasn't much

waltzing done in rural Island communities until the Second World War. Because

couples orient themselves in a large circle -- each spinning on their own axis

as the circle describes an "orbit" around the room's mid-point --

waltzes are sometimes referred to as round

dances.

Again, the 1970s saw a dramatic

growth in the demand for formalized step-dance instruction (see "Decline

and Resurgence). As instructor and provincial legislator Libby Hubley of

Kensington (Prince Co.) describes it, most of the first crop of step-dance

instructors had previously been teachers of tap, ballroom dancing or highland

dancing. Few had grown up in households where step dancing was a part of daily

life. Since progress had to be shown to parents, and pupils had a need to work

toward specific goals, step-dancing became performance oriented. Routines were

worked out, steps were formalized, costumes were designed, and (through

association with tap-dance) metal "taps" were adopted for most

step-dance performances. There are now about 600 step dance students on the

Island at any given time.

On Fiddle Tunes

Fiddle

tunes are the traditional dance music of the Celtic peoples of the world.

While it is unclear just how far they go back, we do know that these tunes had

certainly achieved a relatively "modern" sound and general method of

presentation by the late seventeenth century. Beginning at that time and culminating

about a century later, collectors scoured the byways of Scotland searching for

traditional tunes, and printed them in extensive collections. Once the older

tunes had for the most part been published, a new breed of dedicated

tune-composers sprang up -- like Niel [ed: sic] Gow (1727-1807) and William

Marshall (1748-1833). Most of these composers were in the employ of Scottish

noble houses, and were asked to compose tunes for special occasions. The last

great Scottish tune composer of this tradition, James Scott Skinner

(1843-1927), earned his living as a music hall virtuoso. Over the years,these

composed tunes were added to the stock of older tunes. They are themselves now

considered "traditional" by all but those few who frequent the pages

of old tune collections.

Most fiddle tunes have two sections

-- one part that stays around the low or mid-range strings of the fiddle

(called the low turn on P.E.I.), and

one that moves up onto the upper strings of the instrument (called the high turn on P.E.I.). The low turn is

usually played first, but there are certain tunes where the high turn comes

first. Plus, there are certain regions (like P.E.I.'s Prince Co.) where

fiddlers seem to like starting many of their tunes on the high turn.

For the purposes of this book I will

generally follow common American practice and refer to the first part of each

transcription (usually the low turn) as Part

A, the second part as Part B, the

third part (if any) as Part C, and so

on. Similarly, a variation on the A part is referred to as Part A', a variation on the B part is called Part B', and so on.

Virtually all fiddle tunes have

four, eight or sixteen measures per part. Generally, each part is played twice

through before proceeding to the next part.

Tune Categories

Fiddle tunes are divided into a

number of sharply defined tuned categories. Let's start with tunes used on the

Island for set-dancing -- jigs, reels and set tunes. All three genres have two beats per measure.

Moreover, all three are played at about the same speed -- at a rate consistent

with a metronome setting of one beat equals about "120."

Jigs

are in 6/8 time (each beat is the equivalent of a dotted quarter note).

Generally, they consist of two repeated eight-bar parts, two non-repeated

sixteen bar parts, or a mixture of the two formats. On P.E.I., a distinction is

made between Scotch Jigs (those which

have sharply defined phrases or consist largely of quarter - eighth note

combinations), and Irish Jigs (those

which are composed largely of streams of eighth notes). Some "Scotch"

jigs included in this collection are "Tea Gardens Jig," "Come

Under My Plaidie" and "Goldenrod Jig." Some "Irish"

jigs include "The Irish Washerwoman," "Larry O'Gaff," and

"The Land of Sweet Erin."

Reels

-- called just fast tunes in many parts of the Island -- are in 2/2 or cut time (each beat is the equivalent of

a half note). They are made up primarily of streams of eighth notes, and it

often takes great skill on the part of the fiddler to "shape" these

notes at speed into a listenable melody. Most reels have two repeated

eight-measure parts, but some of the older Scottish reels (and newer tunes that

emulate them) are made up of one repeated four-measure low turn and a

non-repeated eight measure high turn. Some reels have just two repeated four

measure parts.

All hornpipes have eight bars per part, and they have exactly the same

structure as reels with eight-bar parts. In the Scottish and Irish traditions,

however, hornpipes are performed quite differently from reels. To begin with,

hornpipes in these traditions are played at a much slower tempo than are reels

(that is, at a metronome setting of about one beat per click set at 96).

Second, they are almost always played with swing

eighth notes (see "Playing Directions"), while reels can be played

with straight, dotted, or swing eighth notes.

On P.E.I. and the rest of the Maritimes, however, hornpipes are

usually played at the same tempo and with the same style of note production as

are reels. They have therefore been lumped together with reels into a single

section. Those tunes that were performed in true hornpipe style on the field recordings -- like "Fay's

Hornpipe" and "Bonaparte Crossing the Alps" -- are so marked.

Set-tunes

are cut-time tunes played for set or square dancing that are not considered by Islanders to be reels.

In many parts of P.E.I. these tunes -- which generally contain fewer notes per

beat than reels, and which tend to be bowed quite differently -- are called slow tunes. In the set-tune category can

be found polka-like tunes like "Crooked Stovepipe" and "Let's

Have a Ceilidh," along with simplified reel or hornpipe melodies like

"The Road to India." Also present are versions of popular and

traditional song melodies from various eras that have been converted into cut time dance tunes. Some examples of such conversions are "Darlin' Nellie

Grey," "Silver and Gold," and "Home Sweet Home." Set-tunes can have eight or sixteen bars per

section. Eight-bar parts are always repeated; sixteen bar parts are sometimes repeated.

Waltzes

are tunes for slow couple dancing in 3/4 time.

It is interesting to note that the number of waltzes in circulation has

been increased by converting a number

of slow airs in 3/4 or 6/8 time -- like " The Rosebud of Allenvale"

and "The Massacre at Glen Coe," into dance tunes. In addition, a

number of 3/4 time songs from various eras -- like "The Four Marys,"

and "Little Old Log Cabin For Sale" -- have also been so converted.

Most waltzes have two repeated sixteen bar parts.

Marches

are cut time tunes played at walking tempo (about one beat per metronome click

set at 96). In the Scottish tradition, marches have two distinct formats -- the

pipe march and the fiddle march. The pipe march has four

repeated eight-bar parts. The third part (A') is always an elaboration of the

first part (A), while the fourth part (B') is always an elaboration of the

second part (B). To complete the picture, B' has a four-measure-long second

ending which recalls the last four measures of A. In a fiddle march, on the other hand, there are just two eight-measure parts. The second part

(B) of a fiddle march now has the four-measure-long second ending.

On P.E.I., marches are not used for

dancing. Instead, they are played primarily as opening tunes for Scottish sets (see "Medleys").

In many parts of the Island, therefore, march melodies have been converted into reels and pressed into

service for dance accompaniment. Examples here (in the reels section) are

"Johnny Cope," and "Inverness Gathering `Reel.'" Most of

the tunes played in "march-style" on the Island are fiddle marches.

True pipe marches in circulation tend to be "condensed" (lacking at

least one part) or even pared down to fiddle-march format.

Strathspeys

are difficult to define. They are rhythmically complex tunes in 4/4 time played

in a wide variety of tempos. A strathspey of average tempo would have one beat

(that is, one-fourth of the measure) equal to a metronome click set somewhere

between 100 and 120. They originated in the Strathspey (Spey River Valley)

region of Scotland in the early eighteenth century and were first known as strathspey reels. On P.E.I. and nearby

Cape Breton Island (see "The Island Repertoire") strathspeys are used

primarily to accompany step-dancing. They have essentially the same structure

as reels, although the most common form is a four-bar repeated low turn,

followed by a eight-bar unrepeated high turn. In the Maritimes tradition, it is

customary to follow a strathspey with one or more musically compatible reels.

Airs

are relatively slow-tempo listening tunes. On P.E.I., most of the airs played

have forms and patterns of notes drawn from the dance tune tradition. Airs have

a variety of tempos and structures. Many airs are played without a strict

tempo.

Tune Conversions

As indicated above, folk melodies

tend to be elastic in terms of form. On the Island, they are often altered to

suit the need at hand. Song melodies and airs often become set-tunes and

waltzes; marches and strathspeys become reels.

Are there Standard Versions of Tunes?

Because the fiddle tune tradition

has been so well documented for so long, it is easy to get the impression that

each tune has a definitive version. Even a glance through the most common

tunebooks quickly scuttles this notion. In fact, versions of the same tune

appearing in different books often differ in a wide variety of details.

Having had the opportunity to work

with a living fiddling tradition, and to listen carefully in some cases to

dozens of performances of the same tune, I would have to concur with the

general Island attitude on this subject. Islanders feel that there is a core to

every tune -- certain phrases that

must be reproduced in more or less a note-for-note fashion for the tune to

retain its identity. There are other portions of a tune that each fiddler is

permitted to play in his or her own way (see "Individual Styles and

`Twists'.")

Medleys

In the old days a fiddler rarely

changed tunes in the middle of a set-dance figure or step-dance performance.

Nowadays the medley or group of tunes

has become an important feature of Island playing, especially in those areas

closest to Cape Breton. The Island fiddler commonly chooses all the tunes of a

group from the same key, although changes of mode (see "Pitch and Mode") are common. Each tune (with

its repeats) is generally played through twice before moving on to a new tune.

For set-dance accompaniment, a

fiddler generally plays a group of jigs, a group of reels, or a group of

set-tunes. Unless there is a big crowd, a few tunes (each played twice) will

get you through the full length of most set-dance figures.

For stepdance accompaniment, the

fiddler usually plays either a group of reels, or what might be termed a step dance group. In a step-dance group,

one or more gradually accelerating strathspeys is followed by several reels.

At fiddle festivals, ceilidhs, or

musician's gatherings most fiddlers play a group of tunes that is a variation

on the Scottish Set. A Scottish Set

is a medley that consists of at least three different kinds of tunes, all of which usually share the same key-note. It

usually begins with an air or march, and then (like of a step-dance set) it

continues with one or more gradually accelerating strathspeys, and concludes

with one or more reels. Quite often the musician will keep the reels portion of

his set group going until he either runs out of tunes or runs out of energy.

The Island Repertoire

The central core of the Island repertoire consists of perhaps a

dozen tunes -- often referred to as good

old tunes -- that nearly every

fiddler plays. What's more, no Islander ever seems to get tired of playing (or

hearing) them! While there is some variation in different parts of the Island

(see "Regional and Individual Styles"), these tunes can in general be

identified as "Lord MacDonald's Reel," "The Princess Reel,"

"Paddy on the Turnpike," "Pigeon on the Gatepost,"

"Pride of the Ball," "The Farmer's Reel," "Heather on

the Hill," "Sheehan's Reel"

"The Flowers of Edinburgh," "St. Anne's Reel,"

"The Maid Behind the Bar," and "The Mirimachi Fire." In

Western P.E.I., we could add "La Marmotteuse" and "The Ottawa

Valley Reel." In Eastern P.E.I., we could add "Homeward Bound,"

and "Jerome's Farewell to Gibraltar."

This group is far from static. Some

tunes -- like "Lord MacDonald's Reel" and "Pigeon on the

Gatepost" have been good old tunes

for generations, but others are more recent additions. "The Princess

Reel" and "St. Anne's Reel," for example, first appeared in the

1930s, while "Heather on the Hill" did not achieve Island-wide

circulation until the 1950s. Nowadays,

two tunes composed recently by Cape Bretoners -- "Sandy MacIntyre's Trip

to Boston," and "Brenda Stubbert's Reel" -- are fast moving into

this company.

Tune Sources

Most of the Island repertoire, as

previously indicated, derives from a variety of outside sources. Some tunes

arrived with the first waves of Scottish and Irish settlers, others came via

later immigration. Most other methods for acquiring new repertoire depended on

the quick ears and highly developed musical recall of local fiddlers.

Since the late nineteenth century,

many Island fiddlers were forced by a poor local economy to work away for portions of the year, or even

for years at a time. Many young men, for example, spent their winters in the

"lumber-woods" of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Maine and Quebec. Many

others spent years working in major North American cities such as Boston, New

York, Montreal and Toronto. All of these situations created opportunities to

learn new tunes from off-Island fiddlers.

Conversely, there were occasions

when musicians from distant Island communities or even from away participated

in local musical events. Each of these would almost certainly bring with them a

stock of new tunes.

Scottish, Irish, and North American

tune books -- such as Cole's One Thousand

Fiddle Tunes, The Skye Collection,

The Athole Collection and The Scottish Violinist -- were another

major source of new repertoire (See Appendix A). Since the ability to read

music has never been widespread among Island fiddlers, this method often

required the presence of an intermediary. An ear-player would actually spend

extended periods of time with someone -- like a church organist -- who had the

ability to read music. The latter would then play tunes from a book until the

fiddler had them committed to memory.

Like the good old tunes, the Island repertoire as a whole is always

changing. A large number of old Scottish tunes, for example, -- most of the

strathspeys and classic reels like "Archie Menzies" and "The

Bonny Lass of Fisherrow" -- had dropped from general circulation by the

end of the 1920s. In the 1950s, the size of the new circular-formation dance

sets had grown so large that most fiddlers no longer had sufficient stamina to

play reels throughout certain figures, particularly the "grand

chain." This led to a great increase in the number of set-tunes learned.

Most other developments in tune "fashion" since 1930 have followed

local trends in fiddle music broadcasting and recording.

Radio and Recordings

Since so many Island fiddlers had

developed the ability to recall the essence of a new tune in a couple of

hearings, the appearance of fiddle music on radio was bound to have a

significant effect on repertoire. The first fiddling broadcasts reached P.E.I.

about 1930. These broadcasts, which originated in New Carlisle, Québec and

featured Québecois players, were the source of such popular Island tunes as

"St. Anne's Reel" and "The Old Man and the Old Woman." Shortly

thereafter, a number of Island players were tapped for live radio broadcasts

originating in Charlottetown. Fiddler Lem Jay of Mt. Stewart, for example, is

still remembered Island-wide for his annual New Year's Eve concerts, during

which he always played (among other tunes) "Bonaparte Crossing the

Alps" and "Jay's Reel."

Two subsequent developments in

broadcasting were to have a considerable effect on the Island repertoire -- the

rise of Don Messer, and the appearance on radio of fiddlers from Cape Breton

Island, Nova Scotia. In 1939, a New Brunswick native named Don Messer was hired

by CFCY-radio in Charlottetown to anchor its fiddle broadcasts. Within a

decade, Messer's popularity grew to a level where he literally dominated fiddle

broadcasting throughout Canada and the northeastern United States. Messer drew

his repertoire from a variety of sources -- fiddlers he met in his travels, old

tune books, and fiddle recordings from the US. Although Island fiddlers were

quick to learn many of the tunes he popularized -- like "Whalen's

Breakdown," "Little Burnt Potato" and "Blue Mountain

Hornpipe" -- his fiddling style was never very highly regarded by most

old-time players on P.E.I. By and large, they felt he played too fast and too

"straight-ahead," with none of the complexity and drive so prized in

Island playing.

Since the first days of Nova Scotia

radio broadcasting in the mid-1930s, the Cape Breton fiddling style and

repertoire has captivated many Island players. Beginning with fiddlers like

Winston Scotty Fitzgerald, Angus Chisholm, and Little Jack MacDonald -- and

continuing to present day artists like Jerry Holland and Buddy MacMaster --

Cape Breton has become the largest single new-tune source for Island fiddlers.

Many of the tunes played on radio or recorded by Cape Bretoners were old

Scottish tunes, and this led to a resurgence of this material on the Island.

There has also been quite a number of new fiddle compositions coming out of

Cape Breton which have achieved wide circulation, most notably those of Dan R.

MacDonald and Jerry Holland.

Variants

As tunes move among players within

an oral music tradition, become isolated within a region, or migrate between

traditions, they tend to change. As tunes evolve, they form what are known as variants -- entities that are clearly

derivative from a "parent tune," but quite different from each other. An example of two such variants

are the U.S. tune "Leather Britches," and the PEI version of the

Scottish tune "Lord MacDonald's Reel." There are quite a number of

tune variants that are unique to PEI, such as "Jerome's Farewell to

Gibraltar," the Prince Co. version of "St. Anne's Reel," and

"Pride of the Ball."

Memory is often imperfect, and this

can lead to what might be termed mongrels

and hybrids. In a mongrel variant,

portions of two or more tunes are mixed together within the same part. In a hybrid, intact parts from different

tunes are combined together. An example of a hybrid tune is the jig "Paddy

Carrey's Ship*," which combines the low turn of "Paddy Carrey's

Fortune" with the high turn of "The New Rigged Ship." As is the

case with this last tune, sometimes a hybrid can become widely played in its

own right.

"Making" New Tunes

Over the generations, fiddlers on

the Island have been continually composing (making

is the term in local parlance) new tunes. Many of these homegrown Island tunes

have been forgotten, but some of them -- like "The Brae Reel," and

"The Women of Pisquid" -- are still in circulation. Nowadays, there

is still quite a bit of tune-making going on. A substantial number of the

fiddlers we taped had made a tune or two, a few fiddlers had made several

tunes, and at least two players -- Emmett Hughes and Bill MacDonald -- had

become prolific tune smiths. Transcriptions for most of these newer original

tunes have been included in this collection.

Regional and Individual Styles

Because transportation was so

difficult in the old days, fiddlers rarely had the opportunity to hear players

from communities more than a wagon- or sleigh- ride away. At one time, then,

each district more or less had its own style of playing. Today, with improved

transportation and communications, these many local styles have coalesced into

perhaps six regional styles of playing, named for the various Island Counties

-- Northeast Kings, Central Kings, South Kings, Queens, East Prince/Evangeline

Coast, and West Prince. Players from each of these regions differ in terms of

both overall sound and -- to a lesser degree -- repertoire. Capsule biographies

organized by region for the fiddlers whose tunes are transcribed in this book

appear in the section entitled "The Players."

Fiddlers of Northeast Kings Co. near the town of Souris tend to play an ornate,

hard driving style heavily influenced by the Scottish-oriented fiddlers of Cape

Breton. Along with the reels and jigs so popular throughout the Island, they

also play a large number of marches, strathspeys and airs. Their repertoire is

laced with both old Scottish tunes, and the newer tunes coming out of Cape

Breton. They tend to use a relatively abrupt style of bowing, Scottish style

ornamentation, cuts, and snaps ( see "The Prince Edward Island Playing

style"). The pace of their music tends to be on the moderate side.

Fiddlers of South Kings Co. near the

town of Montague play a shuffling, lilting style that reminds me of old

1920s-era recordings of fiddlers from the American South. They play mostly the

"good old" reels and set pieces of P.E.I. Relative to their Northeast

Kings counterparts, their tempos are faster, they have a more rolling style of

bowing, and they use less ornamentation, cuts, and snaps.

Fiddlers of Central Kings Co. near the

towns of Cardigan and Georgetown represent what might be termed an intermediate

style between Northeast and South Kings. Fiddlers from this area play a lot of

the Scottish and Cape Breton repertoire, but in a relatively

"straight-ahead" non-ornamented style with few cuts and snaps.

Fiddlers of West Prince Co. near the towns of O'Leary and Tignish play a style

and repertoire that has a distinct Acadian flavor, with strong ties in terms of

style and repertoire to the fiddle-music scene in neighboring New Brunswick.

The pace of music is quite rapid compared to that found in Kings Co., and the

bowing style is extremely vigorous. In fact, the bow moves so fast and extends

so far afield as the fiddler attacks the strings that it sometimes seems in

danger of flying out of his hand. West Prince fiddlers use few ornaments, cut,

and snaps, but their music is replete with lively rhythms and syncopations.

Fiddlers

of East Prince Co./Evangeline Coast

near the towns of Abram-Village and Wellington blend a bit of the Scottish-Cape

Breton repertoire and rhythmic attack into a largely Acadian-oriented style.

This Scottish influence is due mostly to the influence of fiddler Eddie

Arsenault, who learned a significant part of his repertoire from Cape Breton

broadcasts, and who had the opportunity to play with a number of great Cape

Breton fiddlers while serving in the Canadian Army during the second World War.

Fiddlers from Queens County play what might be termed an intermediate or

central-Island style -- they incorporate some "Scottish" elements

into their playing, but they also tend to have a bit of a syncopated

"French" swing to their bowing.

Two other stylistic considerations

are Island-wide instead of regional. The first involves a distinction made

between Cape Breton-oriented fiddlers and "Island fiddlers." As you

might suspect, the former are those P.E.I. fiddlers who (regardless of region) look

to Cape Breton for both style and repertoire. Island fiddlers, on the other

hand, try to maintain for the most part the tunes and playing style of the era

prior to Cape Breton domination of fiddle broadcasting. Also in the mix of

Island players are the followers and admirers of Don Messer, who emulate his

style and keep his repertoire alive. Most of the latter were bred in Queens Co.

Individual Styles and "Twists"

Within these various styles, there

is tremendous variation from player to player. No two fiddlers hold the

instrument or bow exactly alike, no two conduct the bow across the strings in

exactly the same manner, and no two play any given tune in exactly the same

way. In fact, each fiddler regards it as almost a point of honor to put his

brand (put his own twist is the term

used in local parlance) on each tune that is part of his repertoire. In other

words, there will almost always be a part of each tune where a given player

uses a unique sequence of notes that derives from his own fancy. After all, as

fiddler Leonard McDonald of Emyvale, Queens Co. puts it, "If we all played

exactly alike, it wouldn't matter who played, would it?"

Accompaniment

Accompaniment on the Island begins

with the fiddler's own foot. From the days before extensive instrumental accompaniment,

fiddlers have carried over the habit of affording them-selves rhythmic support

via a stylized foot stomp (usually heel-toe, heel-toe) that accentuates the

off-beat. Much of the time this

foot-stomp is really all the fiddler needs to stay on the beat, even in

situations where an accompanist is not up to the task. Foot-stomping styles

tend to be regional as well, with fiddlers from the western part of the Island

tending to use a more rhythmically intensive two-footed routine (heel-left,

toe-right; toe-left, heel right).

In the old days the accompaniment

instrument of choice was the pump organ, examples of which still grace many an

Island parlor. Pump-organists had worked out an accompaniment style

(unfortunately not heard much nowadays) in which oom-pah piano-like rhythmic

patterns were strategically accented by sustained notes. Today the favorite

accompaniment instruments are piano and guitar. The piano is especially popular

-- and its style of play most highly developed -- in Northeast Kings Co.

Fiddlers' Gatherings

When Island fiddlers meet to have a few tunes, it is rare to have two

melody instruments playing together. Generally, a fiddler will sit himself down

next to the accompanist and play medley after medley until his bowing arm grows

weary (generally about 20 minutes). Then the next fiddler gets up to play. No

one takes it amiss if the same tune is repeated by several different fiddlers

in the course of an evening. After all, each player has his own twist on it!

The Prince Edward Island Playing Style

All regional styles and individual

"twists" aside, there is definitely a distinctive "sound"

that is characteristic of nearly all Island players. This sound is the result

both of shared stylistic features and techniques on the one hand, and of shared

attitudes toward fiddle music on the other. These shared techniques and

attitudes reflect for the most part the conditions presented by the house party

era -- the need to learn in a self-reliant manner, the need to play

effortlessly (and rapidly) for hours on end, the need to be heard above the din

of a rollicking community dance, the need to keep strong time with little or no

accompaniment, the need to make your neighbors (tired though they were after a

hard day of farm work or fishing) get up and dance, the need to please an

"audience" who knew all the tunes and had some very distinct ideas

about how they should be played.

Before we take a look at a few

specific aspects of P.E.I. fiddle technique, I'd like to quickly sketch some of

the cultural attitudes that support them. Specifically, most Islanders --

whether or not they play themselves -- have a fairly clear idea of "what

makes a good fiddler."

First,

as locals express it, a good fiddler must not only have music in him, he must in fact be just full of music. He's got to have excellent musical recall, be

able to keep a large number of tunes in memory, and have the ability to bring

those tunes to life on his instrument. This ability to remember and make music

are considered by most Islanders to be gifts

from the Deity. They are also considered to be inheritable, like hair and eye

color. One common theory on the handing down of the art holds that great

fiddling often skips a generation. Consequently, the most likely group of

offspring among whom the gift might fall would have fiddling grandfathers on

both sides.

Second, a good fiddler's got to play

good and lively. Lively does not mean fast. Instead, it means

playing at comfortable dancing speed, with all the subtle rhythmic nuances of

the local brand of square- and step-

dancing reflected in the bowing. This last quality is referred to as putting a good timing on the music.

Third, a good fiddler's got to play true and avoid "cutting up the

tunes." What this means is that -- all individualistic twists aside -- the

major themes (strains) of each tune as locally known must be played intact.

What's more, notes should not be left out because they are too hard to play at

speed.

Fourth, a good fiddler should have a

sweet, smooth sound. Good players are described as having a lovely sweet music, as being able to take "a dandy sound out

of the fiddle."

Fifth, a good fiddler never stops learning new tunes or ceases

"improving" the ones he knows. Acadian fiddler Eddie Arsenault of St.

Chrysostom, Prince Co. likens the process of perfecting the playing of a fiddle

tune to carpentry:

"It's

like building a house ... [A]fter the rough work is done you gotta put on the

trimming ... [B]ut the fiddler's about the same thing, you see ... When you

start you put mostly the ... note, and then after a while, well you put the

extra note in there in order to put the finishing touch on it -- like finishing

the inside of the house. When you have

the rough work done you got to do the finishing inside."

Techniques of Fiddling

(Examples

referred to are in the book, Fiddle Music

of PEI)

To get that strong sweet tone prized

by most Islanders, fiddlers use a powerful modified "saw-stroke" (one

note per stroke with occasional "slurs"). This stroke is so natural

for most experienced fiddlers that they can virtually do it in their sleep.

Playing is almost always done sitting down. They put a lot of forearm and wrist

into their stroke so that plenty of sound can be obtained without having to

bear into the strings with the hand. They use only a small portion of the bow

for fast tunes to reduce wear and tear on the arm. To allow for easy access by

the bow to the lowest, or fourth string, many players hold the fiddle tilted

down at an extreme angle. Alternatively, some Prince County fiddlers keep the

instrument relatively level, but use their noting hands to periodically tilt

the fourth string into the bow's path.

To decorate their melodies and make

the sound of their tunes sing out, most fiddlers make frequent use of graces (noting-hand ornaments), bowing ornaments, and double-stops (doubled strings). All

three practices owe much to the influence of Celtic bagpiping.

As in other Celtic-based fiddle

traditions, most Island ornamentation is produced by slurring one or more quick

notes off the same bow stroke that produces the

following melody note (see Example 1). Perhaps the most common ornament is

the slow grace (1a). For this

technique, which is similar to a fretted-instrument technique called a

"hammer-on," the player comes on to an important note from below. As its name implies, the slow grace is quite long in duration for

an ornament. Although it is not considered to be an integral part of the

melody, in some instances it can sound as long as a short melody note.

Two other ornaments -- the quick grace, generally comes from above

(1b), and the double grace (1c) are

usually performed by quickly touching an open or stopped sounding string with a free left hand finger. The actual

point at which the string is touched is often not that important, since the

"free finger" does not

fully stop the string. There is also a kind of double grace where the player

ascends or descends to the melody

note via two quick scale steps (1d-e).

A technique I'll call a reverse double-grace (1f), may be unique

to the Island. Here an ornament is created by a quick release and reassumption

of pressure in a finger, without actually lifting that finger off the string.

This "suggests" in succession both the sound of a lower stopped note

or open string, and the original

stopped melody note.

The term hard vibrato was coined by fiddler Paul MacDonald of Charlottetown

(1g). It describes a "scratchy" ornament created by a combination of

an extremely active noting-hand vibrato and a bearing-in by the bow.

Finally, there are a number of

ornaments in circulation made up of three or even four notes (1h-i).

Bowing ornaments (Example 2) are a

variety of techniques used to dress up the tunes. These include snaps, cuts and what I've termed a suppressed stroke. Snaps are a

distinctive rhythmic device imported from Scotland, performed by a quick pair

of alternate-direction bow strokes. They are usually written as a sixteenth

note followed by dotted eighth note (2a), implying that the second note sounds

three times as long as the first. On P.E.I. and Cape Breton, however, snaps are

played in such a way that the second note is only about twice as long as the first, yielding what amounts to a tied-note

triplet (2b). While snaps form integral parts of such Scottish tunes as marches

and strathspeys, they are often integrated into jigs and reels as a form of

syncopation. If played in a jig, they are usually written as an eighth note

followed by a quarter note, as shown in example 2c.

Cuts (2d), known as birls in Scotland, are three quick notes

(two short, one somewhat longer) played in the space of one 4/4 or cut-time

quarter note. They are always performed with a down-up-down motion. They

originated in Scotland to imitate the sound on fiddle of certain kinds of

bagpipe ornaments. Cuts are much more a feature of Cape Breton than of Island

fiddling. In fact, most Island players who put a lot of cuts into their music

come from Northeastern Kings Co. While cuts certainly appear elsewhere on

P.E.I., many fiddlers tend to substitute for them snaps or merely doubled

straight eighth notes (2e).

One fiddler, Dennis Pitre from

western Prince County uses what amounts to an inverted cut (an eighth note

followed by two sixteenths) as a rhythmic device in his tunes (2f).

The suppressed stroke seems to have

originated with Acadian fiddlers, but it has also been borrowed by many of

their Celtic neighbors. It is used as a form of syncopation. On a strong beat

of a tune, the fiddler manipulates the bow in such a way that a

"scratching" sound is heard instead of a pure note. As the tune goes

by, the weak-beat note rings, but the strong beat sounds empty. This creates

the impression that the weak beat note has been accented (syncopated), and the

strong beat note omitted altogether. This is shown by replacing a note-head

with an "x" (2g).

Perhaps the most strongly developed

characteristic of Prince Edward Island playing is the system of elaborate double stops (string-doubling) used by

most of the players. This system -- which probably arose as an attempt to

imitate the droning of bagpipe music -- serves the function of both increasing

volume and dressing up the tune with another level of complexity. Since the

non-melody string in a double stop can be above or below the melody, the

overall effect is of a "harmony line" that corkscrews around the

melody. These double stops fall into a number of categories -- open neighbor strings, anticipated stopped strings, doubled open

strings, and fingering forms. I

have already mentioned that for the

tunes in this book, non-melody "double-stopped" notes are

shown in reduced size.

The double stop involving an open

neighbor string (3a-b) is perhaps the simplest to accomplish. When bowing a

melody note, the fiddler merely takes the higher or lower neighbor along for

the ride. This is a common feature in particular of key-of-A tunes, where the

open first string (E) is played along with many second string notes, and the

open second string (A) is played along with many first string notes.

Anticipated stopped strings (3c-d)

are more or less reversed instances of open neighbors. In other words, the

fiddler has a melody note on one string but anticipates

that his next act is to stop a note on a neighbor string. If he likes the

combination, he will stop that neighbor string early and play it as a double

stop with the melody string. Both kinds of double stopping mentioned thus far

create a droning effect, analogous to that produced on the bagpipes.

Doubled

open strings are employed for more force and emphasis on the open note. The

player in effect "doubles" the sound of the open string by finding

the same pitch on the lower neighbor string. The two strings are then played

simultaneously. In this book, a doubled open string is written as a note with two opposing stems (3e-f).

One common Island practice is to play a slow grace into the stopped member of a

doubled pair (3g).

Two-string fingering forms are used

almost universally on the Island. These amount to fingering patterns that yield

nice-sounding double stops. Each key -- and each "chord" within that

key -- has its own distinct group of these fingering forms. Examples of

fingering forms for the keys G, D, and A are shown in example 4. Note that some

forms include open strings (examples marked "(a)") some are two

finger forms (examples are marked "(b)"), and some involve bridging, or holding down parallel

points on adjacent strings with a single fingertip (examples marked

"(c)"). Note that many fingering forms yield combinations of tones (intervals) known as thirds or sixths.

Because these tone-combinations are the building blocks of chords, use of

fingering forms tends to give the music a very full sound, even when

unaccompanied.

Note that bridging at A and E on the

low strings is used nowadays as a substitute for a once commonly employed scordatura (alternative tuning) called high bass and counter, (AEAE). Other

fiddle tunings used included high bass

tuning (ADAE), and high counter

tuning (GEAE).

Fingering

forms also serve Island fiddlers in a variety of other ways. First, they

provide convenient way-stations throughout the tune, analogous to the use of

chord forms on fretted instruments. Second, fingering forms are used -- again

like fretted instrument chord forms -- to increase the sonority of the

instrument through sympathetic vibration. In other words, even when only a

single string is bowed, its neighbor will also ring slightly at the pitch

stopped in the fingering form. Third,

their use makes certain kinds of otherwise difficult passages easy to play --

especially those made up of quick arpeggios

(broken chords) such as the low turn of "The Princess Reel." Fourth,

fingering forms are used to signal the accompanist what key is in the offing.

To indicate the key of G, for example, the fiddler runs his bow back and forth

across the tones G-B (marked "(b)" on the Key of G line); to indicate the key of D, the fiddler plays the

tones D-F# (marked "(b)" on the Key

of D line), and so on.

Some Important

Island Fiddlers Active in the Early 1990s

On P.E.I. Nomenclature: The "Handle"

P.E.I.

was settled by a relatively small number of family and clan groups who tended

to occupy land in the same immediate area. As a result, there were usually

many families in the same area with the same last name. This led to a situation

where several individuals within a radius of a few miles might have identical

first and last names,

e.g., Joe MacDonald, or Joe Arsenault. To avoid confusion, many community

members are referred to by a special name or handle. Most often this consists of the individual's first

name plus the name of his or her father. So if an individual's handle is Joe

Pete, or (in French-speaking sectors Joe à Pierre) everyone knows he is Joe,

the son of Pete (or Pierre). Sometimes this is not enough and the name of the

grandfather must be brought into play. So, if someone is named Joe Pete Simon,

the community knows that Joe is son of Pete and grandson of Simon.

Fiddlers from North-East Kings County

Sterling Baker (b. mid-1940s, Residence: Montague,

Bred: Morell; Occupation: Merchant) learned his first tunes from local fiddlers

while growing up. He started out as a guitarist, and did not take up the fiddle

until his mid-twenties. While not as ornate as many of his Kings county contemporaries,

his playing is exceptionally clean and tasteful. He plays regularly at a weekly

summer ceilidh held at a restoration called the Orwell Pioneer Village.